What is the return on investment for educating employees well-nigh healthy eating and living?

‚ÄúHow do you wipe out the nation‚Äôs heart disease epidemic?‚ÄĚ Those were the opening words to an editorial by Dr. Michael Jacobson, co-founder of Center for Science in the Public Interest, in the October 2005 issue of the charity‚Äôs Nutrition Action publication. Wrote Jacobson, ‚ÄúThe weightier tideway I‚Äôve seen is the Coronary Health Improvement Project (CHIP),‚ÄĚ which was renamed the Complete Health Improvement Program and then most recently, Pivio. CHIP tells people to eat increasingly whole plant foods and less meat, dairy, eggs, and processed junk. It is considered to be ‚Äúa premier lifestyle intervention targeting chronic disease that has been offered for increasingly than 25 years.‚ÄĚ Increasingly than 60,000 individuals have completed the program, which I discuss in my video A Workplace Wellness Program That Works.

Most CHIP classes are ‚Äúfacilitated by volunteer directors, sourced primarily through the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, who had an interest in positively influencing the health of their local community.‚ÄĚ Why the Adventists? Their ‚Äúhealth philosophy is built virtually the holistic biblical notion‚ÄĚ that the human soul should be treated as a temple. What‚Äôs more, many CHIP participants are Adventists, too. Is that why the program works so well? Because they have faith? You don‚Äôt know until you put it to the test.

Researchers looked at the influence of religious troupe on responsiveness to CHIP, studying 7,000 participants. Even though Seventh-Day Adventists (SDAs) make up less than 1 percent of the U.S. population, well-nigh one in five CHIP-goers were Adventists. How did they do, compared with the non-Adventists (non-SDAs)? ‚ÄúSubstantial reductions in selected risk factors were achieved‚Ķfor both SDA and non-SDA,‚ÄĚ but some of the reductions were greater among the non-Adventists. ‚ÄúThis indicates that SDA do not have a monopoly on good health‚Ķ‚ÄĚ

Middle class, educated individuals moreover disproportionally make up CHIP classes. Would the program work as well in poverty-stricken populations? Researchers tried to reduce chronic disease risk factors among individuals living in rural Appalachia, one of the poorest parts of the country. ‚ÄúConventional wisdom has been that each participant needs financial ‚Äėskin in the game‚Äô to ensure their considerateness and commitment‚ÄĚ to lifestyle transpiration programs. So, if offered for self-ruling to impoverished communities, the results might not be as good. In this case, however, the ‚Äúoverall clinical changes in this pilot study [were] similar to those found in other 4-week CHIP classes throughout the United States,‚ÄĚ suggesting CHIP may have benefits that ‚Äúcross socioeconomic lines‚ÄĚ and are ‚Äúindependent of payment source.‚ÄĚ So, why don‚Äôt employers offer it self-ruling to employees to save on health superintendency costs? CHIP is ‚Äúdescribed‚Ķas ‚Äėachieving some of the most impressive clinical outcomes published in the literature,‚Äô‚ÄĚ including ‚Äúclinical benefits of the intervention, as well as its cost-effectiveness…‚ÄĚ

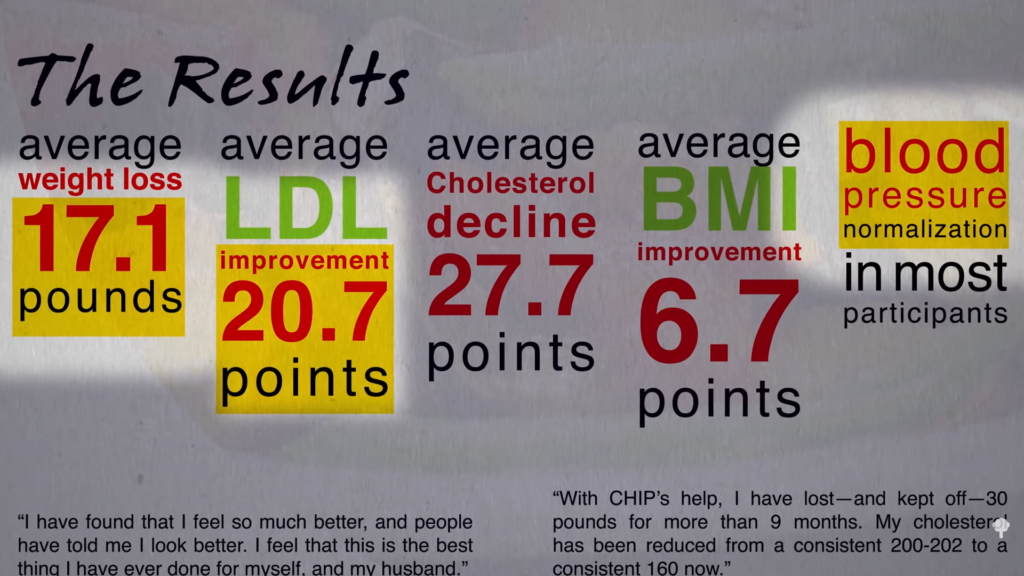

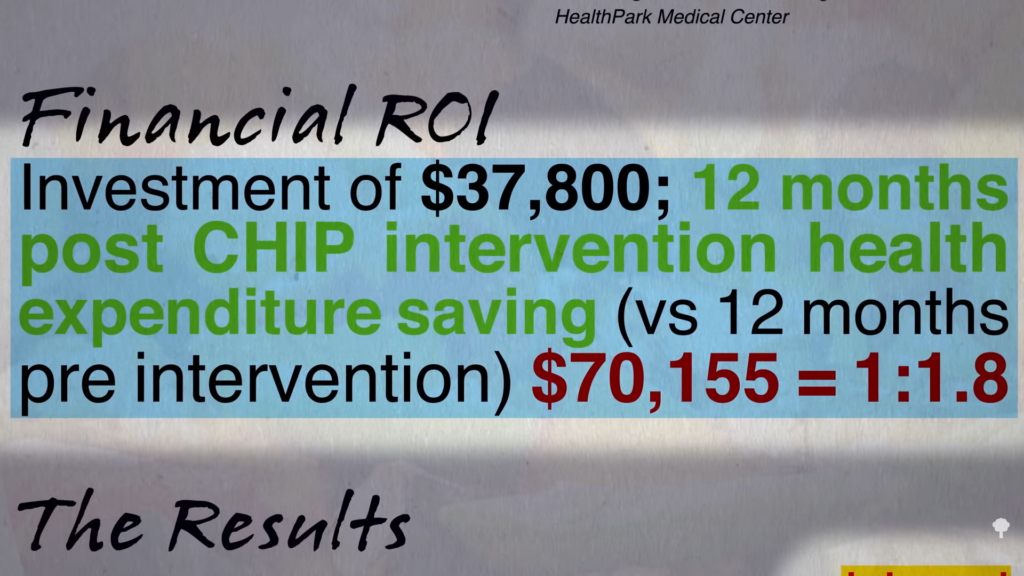

Lee Memorial, a health superintendency network in Florida, offered CHIP to some of its employees as a pilot program. (Sadly, health superintendency workers can be as unhealthy as everyone else.) As you can see unelevated and at 3:05 in my video, they reported an stereotype 17-pound weight loss, a 20-point waif in bad LDL cholesterol, and thoroughbred pressure normalization in most participants. Lee Memorial initially invested well-nigh $38,000 to make the program happen, but then saved $70,000 in reduced health superintendency financing in just that next year. How? Because the employees became so much healthier. They got a financial return on investment of 1.8 times what they put in.

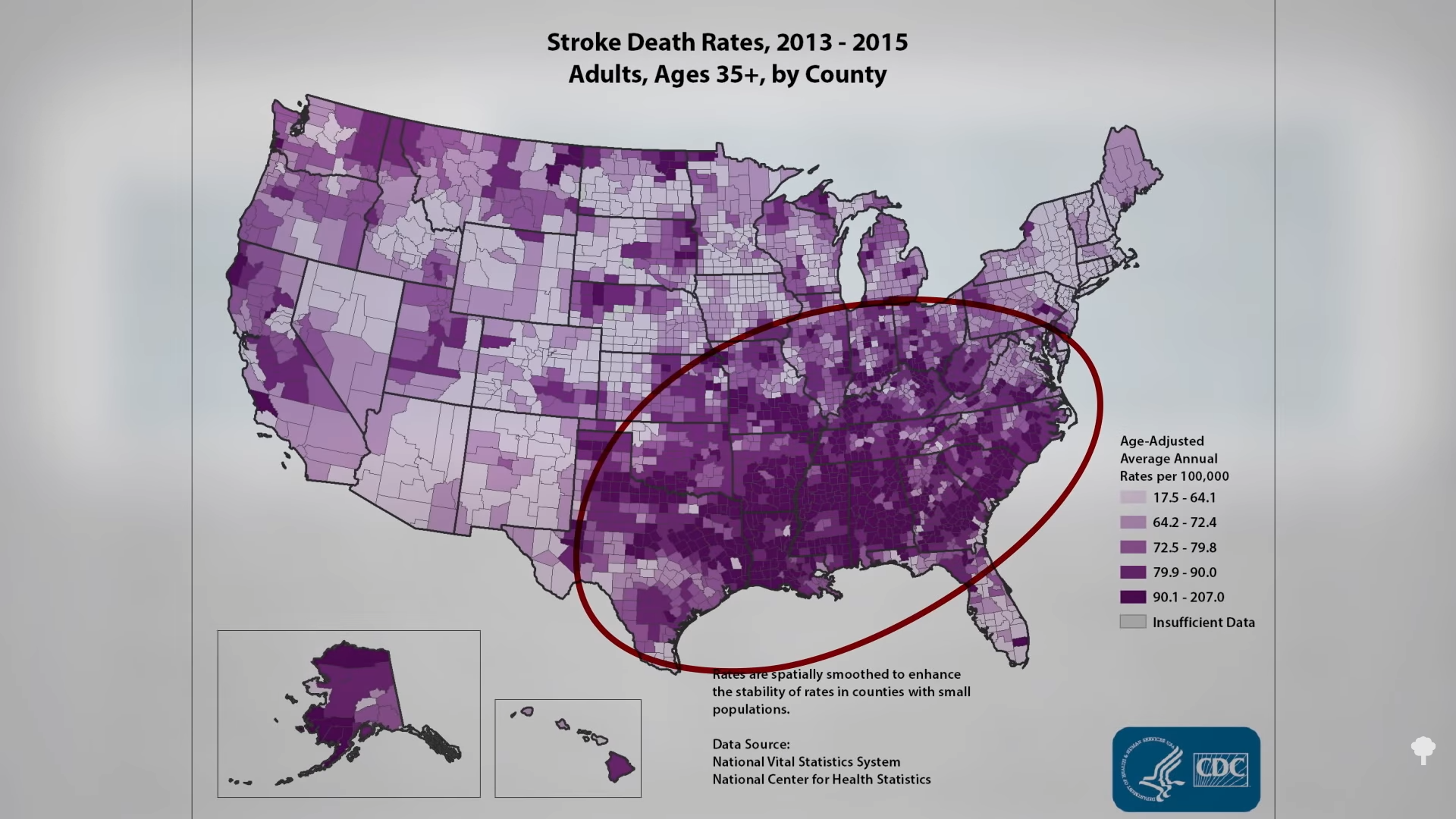

There hadn‚Äôt been a return on investment (ROI) study in the peer-reviewed medical literature until Dexter Shurney stepped up to the plate and published a workplace study out of Vanderbilt. ‚ÄúThere was a upper stratum of skepticism at the planning stage of this study that zippy engagement could be realized in a sizable portion of the study group virtually a lifestyle program that had as its main tenets exercise and a plant-based diet.‚ÄĚ Vanderbilt is, without all, in Tennessee, smack dab in the middle of the Stroke Belt, known for its Memphis ribs. (You can see a graphic of ‚ÄúStroke Death Rates‚Ķby County‚ÄĚ by the Centers for Disease Tenancy and Prevention unelevated and at 3:55 in my video.) Nevertheless, the subjects got on workbench unbearable to modernize their thoroughbred sugar tenancy and cholesterol. They moreover reported ‚Äúpositive changes in self-reported physical health and well-being. Health superintendency financing were substantially reduced for study participants compared to the non-participant group.‚ÄĚ For example, nearly a quarter of the participants were worldly-wise to eliminate one or increasingly of their medications, so they got well-nigh a two-to-one return on investment within just six months, providing vestige that just ‚Äúeducating a member population well-nigh the benefits of a plant-based, whole-foods nutrition is feasible and can reduce associated health superintendency costs.‚ÄĚ

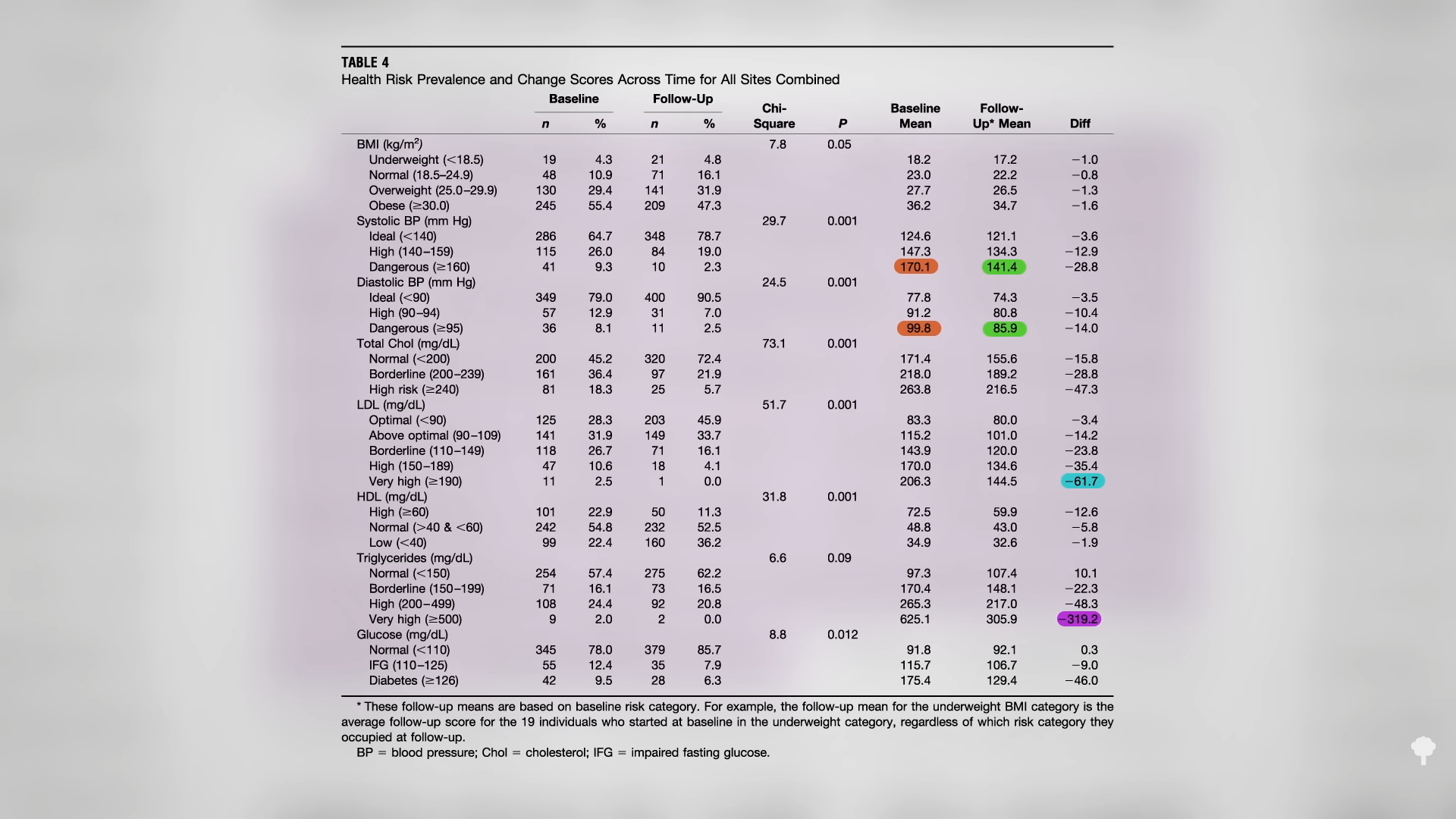

The largest workplace CHIP study washed-up to stage involved six employee populations, including, ironically, a drug company. The study included a mix of white-collar and blue-collar workers. As you can see unelevated and at 4:40 in my video, there were dramatic changes experienced by the worst off. Those starting with thoroughbred pressures up virtually 170 over 100 saw their numbers fall to virtually 140 over 85. Those with the highest LDL cholesterol dropped 60 points and had a 300-point waif in triglycerides, as well as a 46-point waif in fasting thoroughbred sugars. Theoretically, someone coming into the program with both upper thoroughbred pressure and upper cholesterol might ‚Äúexperience a 64% to 96% reduction in overall risk of myocardial infarction,‚ÄĚ a heart attack, our number one killer.

As Dr. Jacobson terminated in his editorial in Nutrition Action, ‚ÄúFor the forfeit of a Humvee, any town could have a CHIP of its own. For the forfeit of a submarine or a sublet subsidy, the unshortened country could get a CHIP on its shoulder.‚ÄĚ